Month: September 2020

CNF: Save for a Rainy Day

by Chidera Ihekereleome-Okorie

Because you know an idiom or two, don’t mean you should use or say them. But if you must, ruminate before you do. Because you see the sun often, don’t mean others do. You say save for a rainy day, but there are things you are oblivious to because you don’t look deep enough. And when you do look, it is empty of compassion. Though you are not a surgeon, you do with your eyes what a scalpel does to the body—slice. You are not searching for a tumour, but even if you were, it is not to remove it. You are searching for reasons—a smoke too long, a drink too much, a string of fellatios.

You always find, but though it be insufficient, all that matters is that you find grounds to hold them responsible for their trauma. But I thought you should know; there are people for whom every day is a storm. Escaping the lightning is all the saving they know. Some only get umbrellas with cavities matching the colour of sky. Do not expect them to not get drenched. For some, saving is survival, and survival is not for a rainy day. It is for every storm, for every lack, for every day.

Chidera Ihekereleome-Okorie is an emerging poet who lives in Nigeria. She writes poetry because it helps her understand the world and the reason she is in it at this time. Her work has appeared in perhappened mag. Find her on twitter @chideraIheke.

See what happens when you click below.

What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “Save for a Rainy Day”? I first wrote this poem for a contest. I submitted it, but I never received feedback. The night I wrote this poem, I felt it was incomplete, but I was not sure what was missing. The final version is same as the first, except in its arrangement. It is incredible how the same piece now has an entirely opposite feel. It is one of the best things I have written. The intention of this piece is to stir up some humanity in the reader. It is a reminder to be kind because what good does it do if you are not? by Pamela Painter For a while I kept a list. I don’t know why I started it because when I started it I was already pretty deep into numbers and it was embarrassing, looking back, not to remember some last names, and even the first name of one man on the list. He was X, with the year and party where we met. Then I worried that someone would find my list and be appalled that I couldn’t remember last names. Then I wondered if that was all the someone would be appalled about? What about the dives and bars. Conferences. Artist residencies. Concerts. Hikes. Match.com… What was the list for? Why did my list make no distinction between a one-night stand and the first man I was married to for 13 dreadful years? Never mind the name of my second husband whom I loved? I didn’t use a code: No code for education, salary, cultural interests, weight, size, length, length of the attachment, who broke up with whom—if indeed the “attachment” was long enough to warrant a break-up. One-night stands do not. On the other hand, there is the second night of a one-night stand. You would think it doesn’t call for or deserve rules for disengagement. But it does. PAMELA PAINTER is the author of four story collections, Getting to Know the Weather, which won the Great Lakes College Award Award for First Fiction, The Long and Short of It, Wouldn’t You Like to Know and Ways to Spend the Night. She is also co-author with Anne Bernays of What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers. Her stories have appeared in The Atlantic, Five Points, Harper’s, Kenyon Review, Matter Press, New Flash Fiction Review, Ploughshares and SmokeLong Quarterly, among others and in numerous anthologies, such as Sudden Fiction, Flash Fiction, From Blues to Bop:A Collection of Jazz Fiction, MicroFiction, Nothing Short of 100, and New Micro. She has received grants from The Massachusetts Artists Foundation and the National Endowment of the Arts, has won three Pushcart Prizes and Agni Review’s John Cheever Award for Fiction. Painter’s stories have been presented on NPR, and on stage in Los Angeles, New York City and London by Cedering Fox’s Word Theatre Company. Painter’s new collection of stories, Fabrications: New and Selected Stories, is due out from Johns Hopkins University Press in 2020. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “Her List”? Someone in the group of writers staying at my Cape house suggested this as a story idea and we all wrote our story on the spot, and then read them out loud to much hilarity. I don’t know why, but it pleases me that I use third person in the title, but first person in the story. by Brittany Oppenheimer Dear Brittany Remember that show you love? The one that shaped your life and made you decide to become a writer? Well, if you don’t, the name of that show is Gilligan’s Island. Remember back in 2015 when you became depressed? I do. All your life, you wanted to be a vet technician. You loved animals. You wanted nothing more than to help and save their lives. That’s what you wanted, right? It was only when you took biology that you realized this wasn’t something you wanted to do, forcing you to think that your life had no purpose. Hey Brittany Remember when you started watching Gilligan’s Island that year? I do. You watched every episode, laughing at the funniest moments and crying at saddest ones. I was there when you cried for Gilligan over the thought of him killing himself. This reminded you how useless you were. How you figured that no one would miss you if you were dead. You were such a tortured soul. You always thought no one understood you. That’s why your connection to this show was so special, because if your family didn’t understand you, your favorite show always did. Brittany Do you remember when you fell out of love with this show? I do. I remember your last semester of community college when you had to take a theater class. You were so excited to show everyone why a single frame from one of the episodes was so important to you. You admired the scenery, you admired the effects, you wanted to explain why you loved this show and why this scene had so much meaning to you. Instead of admiring your taste in film, they laughed at you instead. Every student made fun of how Gilligan looked and it made you sad. It made you embarrassed that you liked the show at all. No wonder you stopped talking about it. No wonder you stopped watching it. The show changed your life, set your course to become a writer, and they laughed at you for it. No wonder it took years for you to get back into it. You hated that you lost your innocence, your sense of love for film became tarnished forever. Hello Brittany, this is Innocence. The world is cruel. I know, I was there. I remember seeing so many people making you lose your way. Questioning what you should love and what you shouldn’t. Don’t be a fool. Never let anybody change you because, let me tell you something— If a show gets you to laugh for a day, it makes you human. I know that no amount of hatred can change you now because your heart has been given to a boy that understands what it is like to be truly loved— His name is Gilligan, Love Always Brittany Ann Oppenheimer is a writing studies major at Bridgewater State University. She loves animals, music, rusty basement smells, and writing for fun. Brittany recently has been published in The Y Syndrome Magazine and hopes to graduate with her bachelor’s degree during the spring of 2021. She cannot wait to return home to see her dog Kassie and two cats Loki and Binx after the end of each semester. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “The Extinct Island”? Honestly, I wrote this piece within an hour which is what fascinates me the most. I was actually trying to send this story to another publication which was about to close at midnight. I wanted to write and submit something quickly that inspired me, so I wrote about Gilligan’s Island and sent it to them around 11PM. I just find it funny sometimes that the pieces I work only an hour or two on get published and the stories I work on for days at a time continue to be stuck in limbo. The truth is, I love film. I love talking about the obscure stuff that most people either don’t remember or never heard of before. That includes black and white television shows that never got their time in the sun. I think that is the inspiration of this piece. To prove shows like this can be meaningful in one way or another, no matter how absurd it seems to be in the end. by Erika Kanda Erika Kanda lives in Northern Virginia, USA with her partner. She holds an MA in literature, an MFA in creative writing, and a cat in her lap as she types. She loves hot press paper, matcha macarons, and all things speculative See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “The Accident”? My grandma’s house is full of accidental antiques, because she cares for things so well. That’s how, when I went to visit her over a long weekend, we were able to spend our time together looking through the past. Her paper ephemera is all in crisp condition, and she showed me those snippets of her life –report cards from the 1940s, a hairdressing license from 50s, court proceedings from the 80s, and even typewritten letters to herself from the 90s. In one of these letters, she questions how she suffered a severe personality change and brain injury “from that car accident they say was in July of 1986.” I remember, as a curious child, asking others about the accident. It wasn’t until reading her letters I realized that she had to ask too. The two of us have only heard stories about what happened – about how and who she used to be. In drafting “The Accident,” I’ve tried to recreate that weekend we spent together: piecing together the timeline and fallout of something incomprehensible. I love my grandma as the kind and caring hero she’s always been to me. But when I told her how glad I was she didn’t die, she didn’t smile back. She put her papers away softly and said, “I did die. I just can’t remember.” by Joey Kim Church was the one place in town where Koreans were the dominant culture. I remember sitting in silence next to my mother while she prayed in a language I wish I knew. I sat with her during service until I was forced to go to Sunday School. It took us thirty minutes via car to get to church in Youngstown, and Youngstown was different from where I lived. It had factories, sidewalks, nonwhite people, truck stops, and bus stops. The houses looked older, historical even. It was the one time a week when my mother wore her dress suits or fanciest clothes. My sisters and I wore white-collared dresses, off-brand saddle shoes or Mary Jane’s from Payless, and once we started getting money for chores, white purses. We had to tithe part of our chore earnings as offering. After church service when the adults were meeting about bible study or missions or whatever they did, the kids played in the parking lot or church basement. We weren’t allowed to go anywhere else. One day after service, after the free donuts and coffee, the adults went upstairs to the sanctuary, leaving the kids to play. My two older sisters were hanging with friends their age, and I was watching Esther, our baby sister. She was three years old. Esther wanted to play. She wasn’t allowed to go outside, so I wanted to entertain her. I tickled her and made funny faces that she tried to mimic. “Haha, you’re silly!” she exclaimed, pointing at my air-blown face. “I wanna play tag!” “Ok!” I said, jumping up. “Tag, you’re it!” she cried out, running toward the church kitchen. I gave her a head start, and I got up to pretend to chase her. Pretending is easy for us Asian Americans. Pretending to be white by sounding like them, dressing like them, earning money like them. Audre Lorde said in 1980, “We have all been programmed to respond to the human differences between us with fear and loathing and to handle that difference in one of three ways: ignore it, and if that is not possible, copy it if we think it is dominant, or to destroy it if we think it is subordinate.”1 Us Koreans have chosen the second: “copy it if we think it is dominant,” to the point of assimilation without individual identities. We are a mass of bodies without difference, an “Oriental” balm for healing what Teju Cole calls the “wounded hippo” of white guilt. It was a pretend chase, or so I thought. I looked at her little feet scurrying across the peeling linoleum floor. Her energy was uncontainable. We did circles around the basement, as I tried to tire her out of her Dunkin’ Donuts sugar high. She turned around to look at me and smiled. She continued running, but suddenly tripped on her rubber soles and fell headfirst into the sharp corner of a steel cabinet. Her head was on the floor, blood gushing out of it. I screamed. I screamed again when I picked her up off the floor. My sisters came, saw, and screamed. They went upstairs to get our parents. Korean people gathered around us and spoke in what sounded like the gift of tongues. We took Esther to the hospital. She got eleven stitches in the center of her forehead. My guilt was not a “wounded hippo” kind. I was nine. I did not know how to be white yet. Letting my sister fall marked my arrival into racial adolescence. 1Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 115. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “A Sunday in Youngstown”? The drafting of “A Sunday in Youngstown” started about two years ago, and it is a work I was inspired to write after reading Ibram X. Kendi’s ‘How to Be an Anti-Racist.’ Kendi’s rethinking of the memoir genre as a space for critical race commentary helped me reflect on my childhood as a process of learning my racial and ethnic embodiment before I had the language to understand it. by Julianne Di Nenna J. DiNenna’s poems, essays, and short stories have appeared in: Gyroscope Review; Adanna Literary Journal; Months to Years; Stanford Medical blog; Unruly Women Writers Fourth Volume; Jerry Jazz Musician; Harbinger Asylum; Every Day Fiction; Italy, a Love Story; Susan B & Me; Offshoots; Grasslands Review; as well as others. She was semi-finalist in the Wicked Woman Book Prize competition of BrickHouse Books and has won two literary prizes for poetry. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “Ward Moms”? ‘Ward Moms’ was written during the six-year period of in-again, out-again hospital stays with my teen-aged daughter. My daughter lived in isolation from others, far from where she might catch a loose germ. I quickly re-organized my life to care for her, working full time from hospital wards, finishing a Master’s degree on-line, and writing during sleepless nights. Moms of other children suffering from pediatric oncology were the only people I would see during those six years. We lived through our children, turned to each other for support, while forgetting each other’s names though not each other’s children’s names. When covid-19 broke out, lockdown was a piece of cake for my daughter and me, we had already become too accustomed to isolation. That led me to make the unseen seen, the invisible visible, bring to light the children and their mothers whom the rest of the world would never know or forget about. On 31st December, at a time when everyone else was talking about potential dangers of the “flu” which started far away, I made my daughter look out her window to see the first calendula flower of the imminent new year, an orange-flagged sign of her improving health, I told her. But hélas no, it was rather another sign of climate change, of a winter much too warm, of pending tragedy, of desperation for ward moms. by Amy Bobeda Amy is an artist living in Colorado, pursing her MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics. She’s the founder of Wisdom Body Collective–an artist collective exploring the embodiment of the sacred feminine. She’s also the founder of the Ekphrasis Salon. More about her and her work can be found on her website http://blondewanderlust.com See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “The American Wing collage series”? I came across a book American Paintings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a catalogue of a 1966 exhibition in Los Angeles, the week after my most recent trip to the Met. I am continually struck by the portrait of James Badger, the young boy in the light blue frock coat holding a small bird at his chest. This is the first image I see in the wing of the museum, and the fist image in the catalogue. I shrunk each painting into half or quarter size on the copier, with the end goal to create a two inch collage. I hoped the intimacy and distance would bring some peace of mind, some remark on lineage. The truth is, The American Wing is my least favorite gallery. I struggle each time I wander through the memories of our landscape, wondering how I fit among the pieces as an American artist. Each cut up became a way to imagine a different, perhaps, softer or more overt version of America’s making. A series of twenty two-inch images manifested in a single night. Months later, I found myself slipping words from the New York Times Magazine under the edges, creating a new layer of history, or commentary. Some of the images have manifested in surrealist stories, images of the New York I love, hanging on the periphery. A home away from home, I now realize will be quite different the next time I return. by Avital Gad-Cykman Imagine taking the key for the family apartment in Vienna, the one located in a building already destroyed and rebuilt. Imagine inserting the key into the locked door of the family apartment in Bialystok, to step in and find generations of indifferent neighbors in residence. Imagine someone turning the key at the keyhole of your door in Jerusalem and opening the door before you block it shut. Her face is yellowed like old newspaper. Nobody says anything in any apartment. I don’t disturb the woman sitting on an unfamiliar couch in Vienna, watching a World War II film. I stand still, taking in history, until her adolescent grandson pushes me back out to the hallway and onto the staircase, then closes the door. In a different turn of events, I live inside and they don’t. My key drops on the floor like a tiny bell. I also refrain from interrupting the old couple, with their sons and daughters sitting around a modern table in an ancient living room in Bialystok. They stare at me, then return to their card game. A boy and a girl run in circles around me until I’m caught between their arms and they hurl me back to the cold night. The children can’t speak to me, nor can I hear them. We don’t share a common language. The yellowed old woman enters the kitchen in Jerusalem and sniffs the air. I keep cooking dinner. The smell of her life is long gone from here and her body scent must have changed, but the dog doesn’t bark. Dogs have respect for the people of the house. The woman stands firmly, as if she won’t leave ever again. My children ask who she is. I don’t know what to say. Should she be here? Must we make room? I don’t know, kids. Nobody speaks the same language. Avital Gad-Cykman, the author of Life In, Life Out (Matter Press), and the upcoming Light Reflection Over Blues (Ravenna Press) has published stories in Iron Horse, Prairie Schooner, Ambit, CALYX Journal, Glimmer Train and McSweeney’s Quarterly among others. Her work has been anthologized in W.W. Norton’s International Flash Fiction, Best Small Fiction (Sonder Press) and elsewhere. She lives in Brazil. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “Keys”? The origin of “Keys” is in my visit in Vienna, where my mother was born, and my somewhat shaky sense of belonging. My experience as a refugee’s descendant made me think about refugees from other peoples and the people who expelled them or are simply living in the abandoned homes. We belong with our parents’ abandoned homes, as well as with our new homes and, because wars go on, we may find ourselves on the other side. by Paige Welsh

[Editor’s Note: Click on the triptych below to view it at full size.]

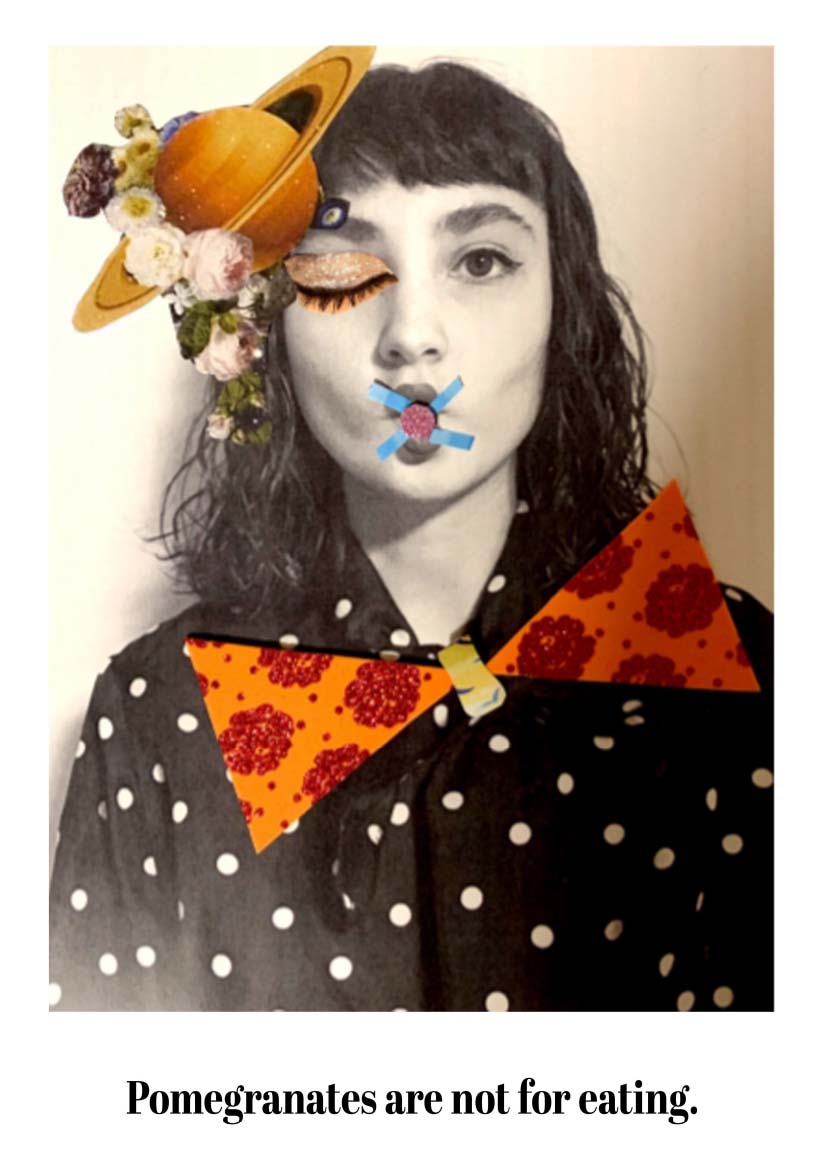

Paige Welsh is a dual English MA and MFA candidate at Chapman University. As an undergraduate, she studied marine ecology and literature at UC Santa Cruz, where her creative thesis won the Chancellor’s Award. She lives in Orange, CA, with her partner, two cats, and too many chickens See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “ Maroonedtr”? “Marooned” is based on an incident I witnessed as a volunteer at The Seymour Marine Center in Santa Cruz. The small aquarium has an open-top tank for petting two long-suffering swell sharks. The idea was to create a sort of exposure therapy for the public who had been coping with shark anxiety since the release of Jaws. I’m not sure the exhibit had the intended result. Many guests touched the sharks on a dare and then yanked their arms away the moment they made contact. The father who held his toddler over the tank was the most extreme example of a common trope: parents forcing their children to touch the sharks to toughen them up. When the sobbing children begged for a reprieve, it was my job to politely speak on their behalf (and the sharks’, who unlike me never volunteered to participate in this social experiment.) I suspect those children are still afraid of sharks. by Amy Bobeda Amy is an artist living in Colorado, pursing her MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics. She’s the founder of Wisdom Body Collective–an artist collective exploring the embodiment of the sacred feminine. She’s also the founder of the Ekphrasis Salon. More about her and her work can be found on her website http://blondewanderlust.com See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “The American Wing collage series”? I came across a book American Paintings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a catalogue of a 1966 exhibition in Los Angeles, the week after my most recent trip to the Met. I am continually struck by the portrait of James Badger, the young boy in the light blue frock coat holding a small bird at his chest. This is the first image I see in the wing of the museum, and the fist image in the catalogue. I shrunk each painting into half or quarter size on the copier, with the end goal to create a two inch collage. I hoped the intimacy and distance would bring some peace of mind, some remark on lineage. The truth is, The American Wing is my least favorite gallery. I struggle each time I wander through the memories of our landscape, wondering how I fit among the pieces as an American artist. Each cut up became a way to imagine a different, perhaps, softer or more overt version of America’s making. A series of twenty two-inch images manifested in a single night. Months later, I found myself slipping words from the New York Times Magazine under the edges, creating a new layer of history, or commentary. Some of the images have manifested in surrealist stories, images of the New York I love, hanging on the periphery. A home away from home, I now realize will be quite different the next time I return. by Başak Yirmibeşoğlu Başak Yirmibeşoğlu is 21 years old Communication and Design student. She is passionate about journalism. She is a freelance writer who focuses on art, fashion, feminism and other topics. Her work has appeared in JeJune Magazine, Tint Journal and DoveTales Journal. She is also an angry feminist and loves to make creepy collages about her activism. You can find her works on https://basakyirmibesoglu.contently.com/?public_only=true. See what happens when you click below. What surprising, fascinating stuff can you tell us about the origin, drafting, and/or final version of “Homage”? It is two series so it has two names: Homage to John Baldessari is a collage series that celebrates John Baldessari’s signature style. This work is a dedication to Baldessari’s conceptual art. It is an absurd collage which integrates with the food we eat and photographs while the fruit loses its function. Homage to Agnés Varda is a joyful and angry collage that reflect women’s mind purely. Agnes Varda is not only my favorite director but also she is an idol for me. I wanted to homage her creative mind. Agnés Varda’s “I tried to be a joyful feminist, but I was very angry.” quote gave inspiration to this collage. It reminds me of all angry feminists who never give up on their struggles.Her List

CNF: The Extinct Island

However, if a show gets you to cry the whole night, it changes your life.

And the Island no longer exists.

~ InnocenceThe Accident

CNF: A Sunday in Youngstown

Joey S. Kim is a scholar, creative writer, and Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo. She researches eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British literature with a focus on Romantic literature, global Anglophone literature, postcolonial theory, and poetics. Her poems have been published in Pleiades: Literature in Context, Burningword Literary Journal, The Hellebore, and elsewhere. In 2017, she received the national Council of Korean Americans’ spoken word poetry prize. Twitter: @joeykimCNF: Ward Moms

American Wing Collage Series (6 of 6)

Keys

Marooned

American Wing Collage Series (5 of 6)

Homage Collage Series

Check out the write-up of the journal in The Writer.

Matter Press recently released titles from Meg Boscov, Abby Frucht, Robert McBrearty, Tori Bond, Kathy Fish, and Christopher Allen. Click here.

Matter Press is now offering private flash fiction workshops and critiques of flash fiction collections here.

Submissions

Poetry, creative nonfiction, and fiction/prose poetry submissions are now closed. The reading period for standard submissions opens again March 15, 2023. Submit here.

Upcoming

04/01 • Lu Chekowsky

04/08 • Robin Turner

04/15 • Beth Sherman

04/22 • TBD

04/29 • TBD